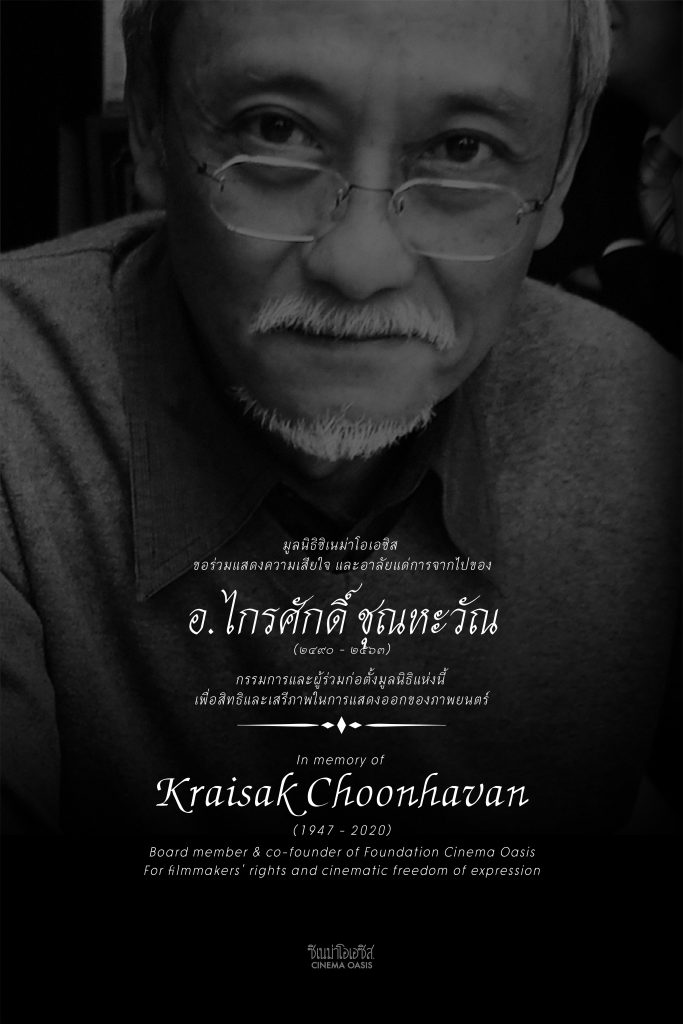

In memory of Kraisak Choonhavan

In memory of

‘Kraisak Choonhavan’

………………………………………………

Filmmaking with Kraisak

As told by Ing Kanjanavanit

I was still a teenager, not even twenty, when I was taken to Kraisak’s house by Caravan band manager Senee ‘Mongkol. Ajarn Kraisak, then a lecturer at Kasetsart University, was still living in the little house over the pond. The occasion was a dinner for people newly returned from the jungle [after the Kriangsak Chamanand government amnesty for ex-communist guerrillas and fugitives]. Some of them were just visiting from the forest. His house was like a safehouse for them, a truly safe refuge because it was situated inside General Chatichai Choonhavan’s Ban Rajakru compound.

I had just finished A’levels in England, so was scornfully regarded as Western-educated spawn of feudal aristocracy. My private reaction, naturally, was one of sardonic resentment: Look at these so-called commies with their Karl Marx on the bookshelves and pink marble bathroom! They have a dining table but they don’t use it. Instead they’re sitting as if it’s an outdoor picnic, on rustic mats on the floor eating somtam, all to the beat of Caravan protest songs. As the night progressed [his mother] Thanpuying [Dame] Boonruen dropped by from the big house in her frilly nightie and proceeded to dance Isan-style to ‘Man and Buffalo’ with handsome young communists. Well, that was fun.

Despite my adolescent cynicism over such ‘pretentiousness’, I really hit it off with Kraisak and have known him ever since. Over the years I heard he was making films with director Kamron Kunadilok and others; one of his films went to the same festivals as mine, such as Hawaii. But I never made a film with him until Teacher Juling Pongunmul was attacked and Kraisak organised an exhibition of her art work to raise funds for her medical care. So I followed him down south when he went to meet with Teacher Juling’s parents in front of the ICU at Hard Yai hospital, and then deeper south to Narathiwas on a fact-finding mission as a human rights senator. I did this because I felt that the Teacher Juling incident was the best portal into the stories of the Southern Unrest, as it was easy for the general audience to relate to.

The camera we used to belonged to Kraisak. Manit Sriwanichpoom was cameraman and I was the soundman. My microphone was on the large side. When he saw it he cried, “Ai Ing, you can’t use that—it looks exactly like a gun, like a war weapon! You’d make us a target.” But we had to use it because it was essential. Kraisak was careful, never going anywhere with military or police escort, so as not to become a target.

The entire crew consisted of the three of us. Once we stayed at the Dusit Thani Narathiwas. As it was a time of highest tension, there was just the three of us in the whole empty hotel. It was eerie, like a haunted tower. When we turned on the bathroom tap, at first only blood-red mud came out. It was obvious no one had stayed there for a long time.

The biggest decision directors have to make is the casting. This is especially important with a documentary. Kraisak was absolutely the right guide for a trip to explore our country’s wounds. He is not some immaculate goody-goody leading man who doesn’t smoke or drink and all that jazz. But he is a really good man in the true sense of the word: empathetic, friendly, warm and so wide open and approachable. People always feel they can trust him and talk to him. If we’d gone there by ourselves, no one would’ve dared to even speak to us and some might’ve shot us. This is why he’s credited as co-director as well as leading man, because I know that without him, there would’ve been no movie.

There were all these lovely surprises, such as running into a man who’d once helped him escape across the border after the coup d’etat against [his father] PM Chatichai’s government. Then there’s the scene of Kraisak getting drunk with his Akha hilltribe chief friend, during which he does the Thai rumwong dance while discussing extrajudicial killings in Thaksin’s War on Drugs. No one else would’ve allowed me to show them in such a jolly state, but because he’s a filmmaker himself, Kraisak understood why this scene intensifies the film, rendering it both more powerful and entertaining. He wasn’t comfortable about it—in fact he was aghast—but he let me shoot the scene and let me keep it in the final film despite personal misgivings. Kraisak truly gets it that life is short but art endures. When all three of us are dead, the film we made together can still be seen; besides, most of the film’s audiences do not know and do not care who we are.

Kraisak firmly believes in the power of art to heal society. Without him, there would be no Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, where we’re having this talk right now. When [Bangkok Governor and later Prime Minister] Samak Sundaravej wanted to build a shopping mall and carpark on this prime site, both of Kraisak’s little daughters joined the sit-in protest right here. The two kids went hunting on the skywalk for signatures to the petition and got tons of support.

Kraisak has given so much of himself to Thai society in the cause of human rights and freedom of expression and is always interested in the opinion of all sides.

One week after we wrapped the ‘Citizen Juling’ shoot, there was a coup d’etat. So now our film has become a record of the atmosphere of the last four months under the Thaksin government—I mean Thaksin directly, himself, not through nominees like his brother-in-law [Somchai Wongsawasdi], his sister [Yingluck] or Samak Sundaravej. We went to take a look and filmed Kraisak as he walked around sightseeing among the tanks, checking out with incredulous amazement the people who’d brought their children to pose for photos with the tanks, because Kraisak is curious and interested in everything and likes to experience all phenomena at first hand.

Even when the redshirts [Thaksin’s supporters] protested, Kraisak also went to see, but the redshirts chased him out and beat him, thanks to the conspiracy to slander him as anti-democratic evil elite royalist what have you.

In this age of Facebook, everyone has a brand. You know, the word branding used to be a sign of slavery: you branded slaves or buffaloes and cows. But now it means Louis Vuitton and Chanel, and every opinion becomes a matter of social status and taste, no different from designer shoes and handbags. If we show up anywhere, it is seen as endorsement of what’s happening, as if everyone’s a soap-selling celebrity. So now everyone refuses to go anywhere.

Thousands of Thais died in the War on Drugs and the Southern Unrest. Why is there still only a single film, fiction or non-fiction, on the situation, to tell the stories of those directly affected? I mean directly about the Southern Unrest; not just films that use the Southern Unrest as a gimmick or local colour.

Possibly no one else has dared for fear of being slandered and blacklisted like Kraisak and me. When Toronto film festival announced that ‘Citizen Juling’ would premiere there, the curator told me they received a deluge of emails from academics for sale—well, he didn’t say they were for sale; I’m the one saying they’re for sale, because they really are for sale. If you want to sue me for saying you’re paid to libel me, go ahead, but kindly reveal the sources of all your funding, where all your grants for seminars and studies come from. These academics for sale staged a witch-hunt demanding that the festival remove our film from its slate, because it is an “anti-democratic film by evil elite royalists’’.

This is probably the first time that such witch-hunting tactics were used by academics for sale to blacklist particular artists, as the Nazis used to do to those they termed ‘degenerate artists’. We have truly arrived at this low point.

Kraisak was the first but since then other artists have been similarly victimized with smear campaigns, such as Sutee Kunavichyanond. Evidently this has been most effective, probably contributing to even the BACC’s truly astonishing decision to exclude Sutee and his ‘History Lesson’ from its pioneers of Thai contemporary art exhibition. On top of which, the show has been titled ‘RIFTS’ [in English only, no Thai title]. Why is Thai contemporary art being defined by the attempt to sabotage, divide and conquer it? Makes no sense to honour witch-hunters over the artists and the art.

You may say it’s okay la; it doesn’t signify if it’s not true. But it can destroy lives. It works because nowadays people don’t look at history and action; they don’t look at our track record, at what we have done in the past. They only see the selfie-made brand.

Kraisak once said something which really moved me:

“I was born in Satan’s womb.”

I understand the weight of history. I feel a duty to record history as it happens because I come from a family that was victimized by and witnessed forbidden history. Kraisak’s grandfather, on the other hand, was a perpetrator of this injustice. So we share a deep bond of mutual understanding which compells us to do what we must do, regardless of consequences.

(Let me just add one thing for Prime Minister Chatichai, Kraisak’s father, with whom I had to fight many environmental battles. He was a gentleman with a big heart who never played dirty tricks on us, never punched below the belt, and was open to facts and reason. For instance, in the Nam Choan Dam and North Phuket Resort at Tha Chatrchai battles, he gracefully retreated, because we were able to debate facts and reason with him. There was no smear campaign to discredit activists and journalists.)

Kraisak is probably the only person I’ve ever met who’s descended from perpetrators yet is open to accept the truth. He is never defensive of his family’s actions in order to shield his relatives from the facts of American Cold War history in Thailand.

Not long ago, Kraisak actually asked me to take him to meet the children and grandchildren of my great-uncle Chit Singhaseni, King Rama VIII’s royal page, who was executed in the King’s Death Case. “I want to beg forgiveness from them,” Kraisak told me, even though he himself had no part whatever in that great wrong. But he still felt guilty, because he is in touch with every one of his beloved country’s wounds.

[From the panel discussion ‘Kraisak Choonhavan at 72’ at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre on 16 August 2019]

______________________________________________________

Interview with Kraisak by Ing K

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jWf0aw0fT0g

https://vimeo.com/ondemand/citizenjuling